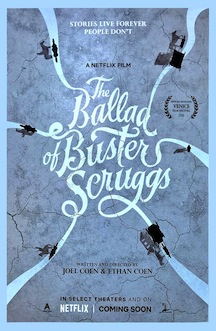

Directed by Joel and Ethan Coen

Country: USA

Taking short rides into the Wild West, the Coen brothers deliver six fabulous vignettes, equally rich in laughs, action, drama, and surrealism. All this is squeezed into their latest feature The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, which portrays on the screen the sagas they keep reading in an old book. Entertaining me for more than two hours, the brothers fabricate unbelievable clashes between settlers and desperadoes in a stylistic intersection between Quentin Tarantino and John Ford.

Most of the stories have unhappy endings, including the first one and my favorite, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, which features a grinning Tim Blake Nelson as a skilled pistolero, bragger, and country singer, literally turned into an angel by the ultra-fast The Kid (Willie Watson), who had recognized him as the most wanted man in the West.

The second story, Near Algodones, presents James Franco as a sly bandit who decides to rob a bank in the middle of a depopulated prairie. The plan goes wrong because the talkative bank teller (Stephen Root) was bold and surprisingly aggressive.

The saddest story is Meal Ticket, which broke my heart into pieces. It unfolds the appalling fate of Harrison (Harry Melling), a young declaimer with no arms and no legs, whose impresario (Liam Neeson) replaces him with a hen that does the math. It’s all about greed and contempt for human life.

The following story, All Gold Canyon, is a pleasure to the eyes. An old prospector (a qualified Tom Waits) digs the soil for gold, finding his gratuity after a lot of work. However, an unscrupulous young cowboy (Sam Dillon) had sneakily followed him, waiting for the right moment to exterminate him and take the prize. Without disclosing more of this adaptation from Jack London’s short story of the same name, I must say you'll likely be smiling by the end.

The Gal Who Gets Rattled, an adaptation of the short story by Stewart Edward Wright, tackles romance between an Episcopalian young heiress, Alice Longabaugh (Zoe Kazan), and a Methodist wagon train leader, Billy Knapp (Bill Heck), who helps her to overcome a financial imbroglio. By the end, there are furious Indian attacks and some spectacular images.

The sixth and last story of the collection, The Mortal Remains, is the most ambiguous as it carries a sort of supernatural predisposition that didn’t work so well for me.

This is cinema peppered with generally convincing acting and the superior visual sensibility of French cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel, who had already worked with the Coens in Inside Llewyn Davis. It is original, brainy, and funny.