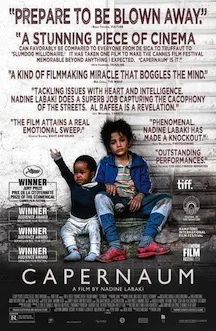

Direction: Nadine Labaki

Country: Lebanon / France / USA

Lebanese director Nadine Labaki’s third feature, Capernaum, is a heart-rending drama focused on the shocking realities of both poor slum inhabitants and migrants living in Beirut. Labaki’s past works has been consistent (Caramel; Where Do We Go Now?), but her directorial career reaches a pinnacle with this saddening tale co-written with regular collaborator Jihad Hojeily and first-time scriptwriter Michelle Keserwany.

The central character, Zain El Hajj (actual refugee Zain Al Raffeea), is a 12-year-old who besides facing the hardships of poverty and neglecting parents, takes in his own hands the responsibility of saving his 11-year-old sister Sahar (Haita Izzam) from an unacceptable marriage. She just had her first period and Assaad (Nour El Husseini), the family’s landlord and local tradesman, is ready to buy her. The kid’s parents, Selim (Fadi Yousef) and Souad (Kawsar Al Haddad), see an opportunity to get a better life in this arrangement. After all, it’s one mouth less they have to feed. Tragic incidences lead Zain to be sentenced five years in prison, but what I was far from imagining is that this astute boy could sue his inconsiderate parents for bringing him into the world.

Prior to his crime and subsequent arrest, Zain had run away from home, finding support in Rahil (Yordanos Shiferaw), an undocumented Ethiopian woman who provides him with housing and food. In exchange, he babysits her little infant Yonas, a target for the malicious Aspro (Alaa Chouchnieh), whose intention is to sell him for adoption.

Simultaneously sensitive and straightforward in her directorial methods, Labaki articulates the moral complexities of the subject matter with an equal share of fascination and depression. She got precious assistance from the pair of editors, Konstantin Bock and Laure Gardette, as well as German-Lebanese cinematographer Christopher Aoun. And, sure thing, it's not possible to disregard the terrific performance of the young new actor, who makes a notable first appearance. Through him, Zain looks real, showing all that street wisdom that no real school would be able to teach him.

It’s all too painful and frustrating, but there are moments of true love and care. My only hesitation has to do with the too optimistic, even naive idea of justice. At once touching and infuriating, the film bursts with irrepressible sadness and deserves kudos for avoiding gratuitous sentimental deflections.