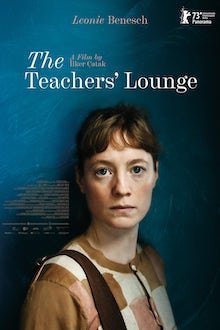

Direction: Ilker Çatak

Country: Germany

In The Teachers’ Lounge, Ilker Çatak’s fourth feature film, a well-intentioned yet naive young teacher, Carla Nowak (Leonie Benesch), finds herself entangled in a troubling situation spurred by a series of thefts at the German public school where she works. This skewed drama unfolds with a growing sense of discontent, occasionally adopting the intensity of a thriller.

Carla embarks on a clandestine investigation using questionable methods, only to discover a flawed scholar system, racial prejudice, and persistent manipulative tactics that hinder genuine problem-solving. The film captures her traumatic experience in a parent-teacher conference, and her difficulties in dealing with pressure from both cynical colleagues and aggressive students.

While the film raises thought-provoking questions about truth and justice, it refrains from providing definitive answers. Despite its noble intention to address contemporary classroom issues, the narrative loses momentum after a promising start, falling into the category of films that are admired more than enjoyed.

In reality, there's an element of outrage in this indirect call to civility, but the film feels somewhat slick and gimmicky. Moments with a stronger sense of real-life authenticity are juxtaposed with others featuring mannered dialogues and postures, causing the narrative to get bogged down in details. The Teachers’ Lounge could have been more involving, given its potential.