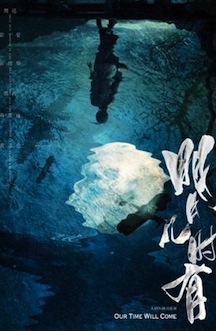

Directed by Ann Hui

Country: Hong Kong / China

Ann Hui is one of the strongest cinematic voices from Hong Kong these days. Even if her last work, “The Golden Era”, wasn’t so striking as one would expect, illustrious dramas such as “Boat People”, “The Way We Are”, and “A Simple Life” still live in my mind.

Her new outing, “Our Time Will Come”, was written by Jiping He (“The Warlords”) according to real characters and events and depicts an important chapter of Hong Kong history, namely, the fight of the local people against the Japanese occupation in the early 40s.

Xun Zhou ("Flying Swords of Dragon Gate") is Lan Fang, a tenacious primary school teacher, who moved by a strong sense of justice and duty, decides to leave her aging mother (Deannie Yip) and the domestic comfort to join the Dongjiang Guerrilla, a special faction created to rescue important intellectuals - artists, writers, scholars, and filmmakers - whose voices were silenced and bodies put under lock and key.

With the schools closed and her fiancé, Kam-wing (Wallace Huo), operating undercover on the enemy side, Lan is easily dragged to the Guerrilla’s missions, becoming a respected captain after receiving an invitation from Blackie (Eddie Peng), a feared leader who convinced her with words of praise and a couple of dumplings.

Everything gets complicated when Lan’s mother decides to actively help her daughter and the cause by passing critical information, ending up arrested and tortured by the Kenpeitai (the military police arm of the Imperial Japanese Army disbanded in 1945).

Ms. Hui attempts to consolidate the realism when simulating a fictional interview with a former young messenger, Ben (Tony Leung), set in the present day and shot in black and white. In the film, this humble man had the privilege to meet the film’s heroine during those tumultuous times and still works as a cab driver.

Even low-key and a slightly stagy at times, the film manages to project this particular story in a way we can understand the wider historical context. Ann Hui fulfills this requirement through a sturdy directorial hand and clear storytelling, even considering her inability to transform “Our Time Will Come” into a thrilling film. In opposition to being a bit too relentless with sometimes wobbly spy moves and episodic brittle war scenes, the film boasts authenticity in its performances, using a legendary symbol of feminine independence and revolutionary resistance to remind us of the sacrifices and efforts put up by the oppressed minorities in response to a cruel occupancy.

The evocative cinematography by Nelson Lik-wai Yu, habitual first choice of Jia Zhangke, is one of the film’s highest pleasures.