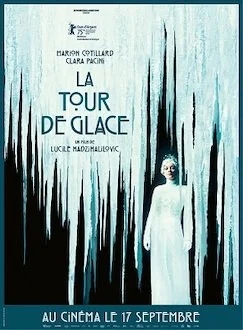

Direction: Lucile Hadzihalilovic

Country: France

Lucile Hadzihalilovic’s new feature, The Ice Tower, is a contemplative and gloomy fairytale that reaches gothic proportions by playing with shadows and immersing itself in dark, anguished atmospheres. However, this mise-en-abyme exercise, set in the ’70s, nearly exhausts itself in artifice. Adopting experimental, surreal, and glacial tones, this fantasy drama strikes with emotional cruelty—a bleak blend of strange passions, obsession, motherless trauma, and inharmonious relationships. The controversial filmmaker Gaspar Noé—Hadzihalilovic’s partner in real life—makes a cameo appearance, while Marion Cotillard reunites with the director 21 years after their first collaboration, Innocence (2004).

The script, co-written by Hadzihalilovic and Geoff Cox, draws an obvious connection to Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale The Snow Queen, while its cinematic influences range from Black Narcissus (1947) to A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935) to The Spirit of the Beehive (1973). Never rushing its narrative flow, The Ice Tower follows a runaway 15-year-old orphan, Jeanne (Clara Pacini), who takes refuge in the film studio where volatile actress Cristina Van Den Berg (Cotillard) is shooting The White Snow. Drawn to one another, they develop a very strange bond.

This is one of the oddest, most outrageous, and most disproportionate films to emerge this year—a beguiling mix of art and fantasy, psychic dissonance, and shattered mirrors that yields yet another intriguingly peculiar experience. It is, however, a difficult film to watch, and not as captivating as Hadzihalilovic’s previous feature, Earwig (2021). Technically well made, it is not particularly enjoyable at its core, limned with bitter rawness and marked by loneliness and despair that can be terrifying. But does its dreamlike, phantasmagoric aura carry us anywhere more profound than the merely artistic? Not quite. The narrative eventually freezes, suffocating without knowing where to go next. It’s a film that transfixes more than it enchants.