Direction: Bi Gan

Country: China / France

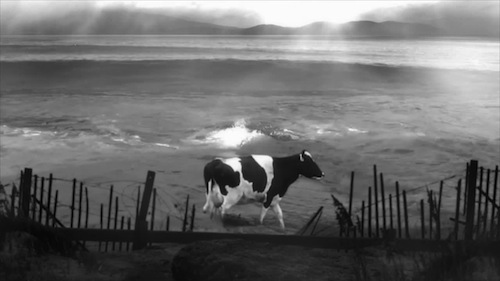

This particular Day’s Journey Into Night has absolutely nothing to do with the famous Eugene O’Neill's play turned into a classic drama film by Sidney Lumet in 1962. Instead, it is an art house effort that marks the second directorial feature film by Bi Gan, a Chinese filmmaker, poet and photographer born in Kaili, Guizhou province.

The follow-up to Kaili Blues (2015) is stylishly rich in influences, carries a good-look charm and an intriguing noir mood that lingers. Like its predecessor, it has the director’s hometown as a point of departure for a dreamy, sort of out-of-the-body experience where false and true memories blur a labyrinthine reality. The director got credit for changing to 3D at some point, after which he shot a nearly one-hour take.

The secluded Luo Hongwu (Huang Jue) talks in his vivid dreams. He calls himself a detective as he searches for Wan Qiwen (Tang Wei), the girl in his dreams, the one who marked his life in such a way that it's impossible to forget her. He doesn’t know what happened to her since he left Kaili 12 years before. However, his father’s death forces his return to that city, an opportunity to investigate more about his mysterious former lover.

This man is willing to undertake wacky trips where several encounters with strange people occur under intriguing ambiances. There’s an abandoned old house transformed into a shallow pool by a leaking ceiling, a rusty wall clock with valuable info inside, a green book with an inspiring love story, a decrepit porn theater with a passageway to a secret basement from where it’s difficult to find a way out, a dark place for gaming where he gets locked up with a girl from his hometown… all these elements push us to walk through a gauntlet of sensory, obfuscatory mystery. If the cinematography is great, the score led by Jia Zhangke’s first choice, Lim Giong, is no less essential.

The film occasionally strains to connect in all its languor and wistfulness, but when it does, it can be fascinating. This is a minimal story structured with deliberate entanglement; therefore, don’t expect things to be served easily. It’s puzzling like Tarkovsky, romantic like Wong Kar Wai, and painful like Tsai Ming Liang.

Bi Gan presents us impasses and ambiguities along the way that by no means are resolved. I take my hat off to him in terms of filmmaking, yet the experience would have been better if the script had a less blurred nitty-gritty and more bite.