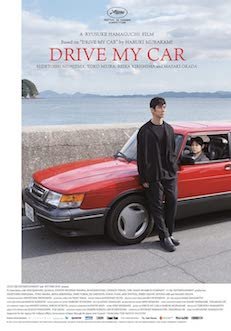

Direction: Ryusuke Hamaguchi

Country: Japan

This strangely affecting drama directed by Ryusuke Hamaguchi produces a flash of quiet brilliance that resonates steadily throughout the engrossing three-hour session. Slowly mesmerizing, Drive My Car brings many rewards in what is an interesting adaptation of a short story by the Japanese writer Hakumi Murakami. Hamaguchi, who co-wrote with Takamasa Oe, modified it with cleverness and gave it extra depth by virtue of delicate gestures and a timeless grace.

The self-aware and fluid storytelling is at the base of huge moments of cinema, bringing personal life drama and professional theater together, as we follow the sad path and ultimate liberation of Yusuke Kafuku (Hidetoshi Nishijima), a theater director and actor consumed by loss and guilt. This man lost his beloved wife (Reika Kirishima), a respected screenwriter, shortly after finding out she was betraying him with a younger actor, Koji Takatsuki (Masaki Okada). Two years later, the director takes the latter as his student during a residency in Hiroshima. Chekhov’s play Uncle Vanya is to be performed. Despite the painful memories this situation brings, he finds some relief in his competent new female chauffeur, Misaki (Toko Miura). She is a 23-year-old from a small village in Hokkaido with a complex past and a similar trauma to heal.

This is Hamaguchi’s 2021 double achievement, after having drawn attention with the anthology romantic drama Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy. Despite of the possible traps in the material, he was able to maintain a rigorously unsentimental tone here, and mounted each scene like a virtuoso of restraint with the assistance of cinematographer Hidetoshi Shinomiya.

The film won the Best Screenplay award in Cannes, a totally deserved accolade for setting an incredibly subtle example of cinematic virtuosity and poetry.