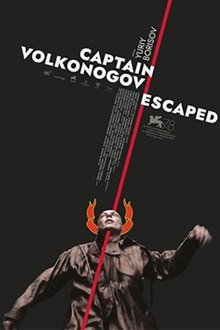

Direction: Natalya Merkulova, Aleksey Chupov

Country: Russia

Tautly written and directed by Natalya Merkulova and Aleksey Chupov, Captain Volkonogov Escaped is a gripping, visceral drama thriller with solid acting and arresting cinematography. It takes the form of a furious post-modernist parable where mystic elements infiltrate a dark, horrific reality denounced at a breathless pace. The film is set against the backdrop of the Great Purge, Stalin’s violent 1938 campaign to solidify his absolutism, which resulted in the arrest, torture and execution of about a million people.

Captain Fyodor Volkonogov (Yuri Borisov) is a high-ranking agent within the law enforcement unit known as National Security Service (NKVD). He’s been a merciless torturer and executioner for years. However, by observing the madness around him - innocent people confess crimes every day under heavy torture while young agents can’t stand the pressure of their duties and commit suicide - he decides to escape the governmental organization in order to save his soul. He sets off on a desperate and unstoppable mission in seek of forgiveness, which, urged by the ghost of his late best friend and colleague ‘Kiddo’ Veretennikov (Nikita Kukushkin), becomes more important than life itself. But will someone within the victims’ families be able to forgive a monster like him?

Carrying a rare intensity in the narrative, which recalls literary works by Dostoyevsky and Bulgakov, the film is overwhelmingly painful; an original moral tale that, in the guise of a survival thriller, seeks for a trace of humanity. This is grim yet powerful cinema.