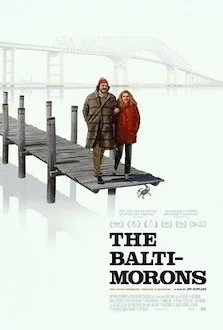

Direction: Constance Tsang

Country: USA

American filmmaker Constance Tsang makes a very positive impression with her feature directorial debut, Blue Sun Palace, a wistful contemporary drama starring seasoned Taiwanese actor Lee Kang-sheng—a frequent collaborator and first choice of acclaimed director Tsai Ming-liang—alongside Wu Ke-xi (The Road to Mandalay, 2016) and the still under-the-radar Haipeng Xu.

The story revolves around the unexpected bond between two Chinese migrants living and working in Queens, New York. Stricken by loss and loneliness, Cheung (Lee) and Amy (Wu) feel strangely connected after the murder of Didi (Xu), Cheung’s lover and Amy’s best friend. As their shared grief draws them closer, their emotional fragilities and lingering doubts complicate the connection.

Blue Sun Palace conveys a peculiar sense of belonging and displacement simultaneously, addressing solitude through intimate close-ups and melancholy imagery that sustains a solid narrative core. Absorbing in its languid rhythm, the film uses cultural nuance and contextual detail to explore imperfect relationships and the ways individuals cope with sudden tragedy.

Tsang’s screenplay unfolds organically, and her quiet, sometimes understated presentation of a tentative love story is wrapped in a transfixing mournful atmosphere. Gradually accumulating moments of compassion and somber revelation until it radiates painful loneliness, this offbeat and serious tale of love and death, infused with a dreamlike quality, reaches deep into genuine romantic longing. The mood lingers—recalling the cinema of Tsai Ming-liang—through a spare yet clear narrative approach that offers a poignant portrait of migrant life, likely to make viewers’ hearts beat in sync with its emotional cadence. On the strength of this observant and affecting work, Tsang’s future projects merit close attention.