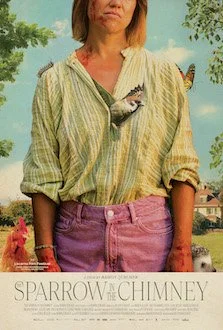

Direction: Ramon Zürcher

Country: Switzerland

In this relentlessly bleak drama written and directed by Ramon Zürcher and produced by his brother Silvan Zürcher, tensions within a dysfunctional Swiss family reach unbearable levels. Without much filter, The Sparrow in the Chimney—the final installment in their “animal” trilogy—goes everywhere except somewhere truly interesting, offering instead a strange sense of liberation that feels excruciatingly numbing. The film is so deliberate and self-absorbed, so enamored with its own bitterness, that it loses sight of emotional resonance.

Controlling and self-destructive, Karen (Maren Eggert) harbors deep resentment toward her outgoing, if traumatized, sister Jule (Britta Hammelstein), and secretly spies on her husband. Her youngest son, Leon (Ilya Bultmann)—a domestic caretaker of sorts—is relentlessly bullied. Her eldest daughter, Johanna (Lea Zoë Voss), is openly defiant and full of disdain. To complete the dismal picture, her husband Markus (Andreas Döhler) is having an affair with their arsonist neighbor Liv (Luise Heyer), who develops a strange, unsettling bond with Karen. The narrative unfolds over two intense days.

Influenced by David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive and echoing the bleak universes of Michael Haneke and Ulrich Seidl, Zürcher fails to justify the film’s pervasive unpleasantness with any fresh insight. Instead, in his eagerness to provoke through both micro and macro aggressions, he more often misses than hits. There’s a lingering sense of perversion that ultimately feels exploitative rather than illuminating, as the film seems to bully its audience with its simmering anger, paranoia, and contempt.

As sordid as it is absurdly overblown, The Sparrow in the Chimney descends into a cruel tangle of hidden desires and family secrets that collapse in a wretched avalanche of excess.