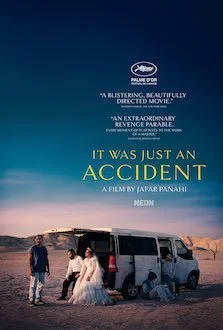

Direction: Jafar Panahi

Country: Iran

Jafar Panahi (Crimson Gold, 2003; Taxi, 2015; No Bears, 2022), the ingenious Iranian filmmaker long targeted by his country’s authoritarian regime, draws directly from his second imprisonment for his 11th feature, It Was Just An Accident. Favoring long takes and dialogue-driven scenes, the film follows Vahid (Vahid Mobasseri), a mechanic falsely accused of spreading propaganda against the regime, who believes he has unexpectedly crossed paths with Eghbal (Ebrahim Azizi), a ruthless, one-legged agent who tortured and humiliated him for years. Consumed by rage, Vahid kidnaps the man with the clear intention of killing him. When doubt begins to creep in, however, he turns to a group of fellow survivors—Shiva (Mariam Afshari), Goli (Hadis Pakbaten), and Hamid (Mohammad Ali Elyasmehr)—to help confirm the man’s identity.

Filmed clandestinely, It Was Just an Accident functions as a straightforward thriller that, despite its lucid dialogue and principled intentions, gradually loses narrative momentum. Blending political courage with cinematic audacity, the film bears the mark of a true fighter, one who insists on distinguishing executioners from victims even when rage and the thirst for vengeance blur moral lines. Panahi approaches these heavy themes—acknowledging wounds that never truly heal—with a tone that oscillates between dark humor and sober drama. He worked with the advice of Mehdi Mahmoudian, himself a former political prisoner who spent considerable time in Iranian jails.

While not a radical departure from Panahi’s earlier work, the film signals a shift toward a more direct approach. The result is a provocative, at times satirical drama whose parts often feel stronger than the whole. It’s a film that actually stands up and shouts, wanting to be noticed, yet its narrative twists are limited, and several key scenes fall short of the emotional impact they seem to aim for. Support for Panahi is unquestionable, but he has articulated sharper and more inventive statements in his previous films.