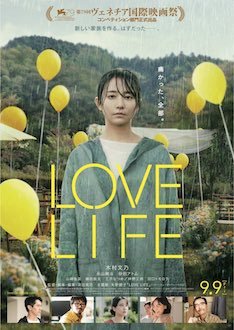

Direction: Koji Fukada

Country: Japan

Shot with the intimacy and formality that is many times associated with Japanese cinema, Love Life is an emotionally complex melodrama rooted in grief, trauma and patriarchy, but branching out into insecurities, reconnections and family subtleties.

Writer, director and editor Koji Fukada (Harmonium, 2016; The Real Thing, 2020) brings us the story of Taeko (Fumino Kimura), and her husband Jiro (Kento Nagayama). The couple works together at the local social service center and is happily married despite Jiro’s father has never approved of their relationship. Taeko has a bright six-year-old son, Keita, from a previous marriage. A shocking tragedy suddenly shakes this family without warning. All of them will have to adapt to the new reality. Keita’s estranged biological father, a homeless Korean man (Atom Sunada), resurfaces shortly after Taeko finds out that Jiro had a fiancée before her, who happens to be their coworker.

Coping with grief and the role of women in the patriarchal Japanese society are not the only central topics here. Loneliness is also very present, clashing with the constant communication - in three different languages - that occurs among the characters. These people are wounded inside and vacillate in several ways when disoriented. We feel them as they breathe the discomfort of their lives in search of love and resilience.

Melancholy infiltrates an acerbic story that employs too much composure for a plot that, even fairly unpredictable, is meandering and not as moving as the director would have intended it to be. Yet, the beautiful image composition comes with extraordinary sharpness and is to be praised - director of photography Hideo Yamamoto worked extensively with Takashi Miike and contributed to Takeshi Kitano’s Fireworks look great.

Fukada signs a drama punctuated with strong sequences of muted disenchantment and discreet humanism. They warn us about the impossibility of controlling life as well as the time required to overcome difficult phases.